The Dover Quad - a colonial pillbox?

Posted: 16 July 2014 17:24

The so-called Dover Quad is a defence work classed as a 'pillbox'; not surprising, given its appearance. However, a new archive discovery has shed some light on the evolution of this oddity.

The name Dover Quad appears to be a post-war descriptor given to provide an identity to these square structures that are scattered around the hillsides of Dover, in Kent.

Yes - you read that correctly - Kent. I do occasionally stray over the border, and I thought that the story appearing in the documents was worthy of some fieldwork, even though my focus remains in East Sussex.

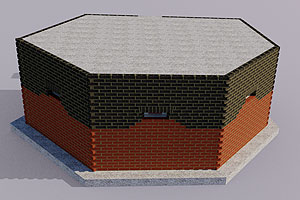

In terms of design, the Dover Quad is no architectural award-winner. The photo below shows a typical example, brick-shuttered concrete with concrete lintels and roof slab. The embrasures of this one have been blocked up.

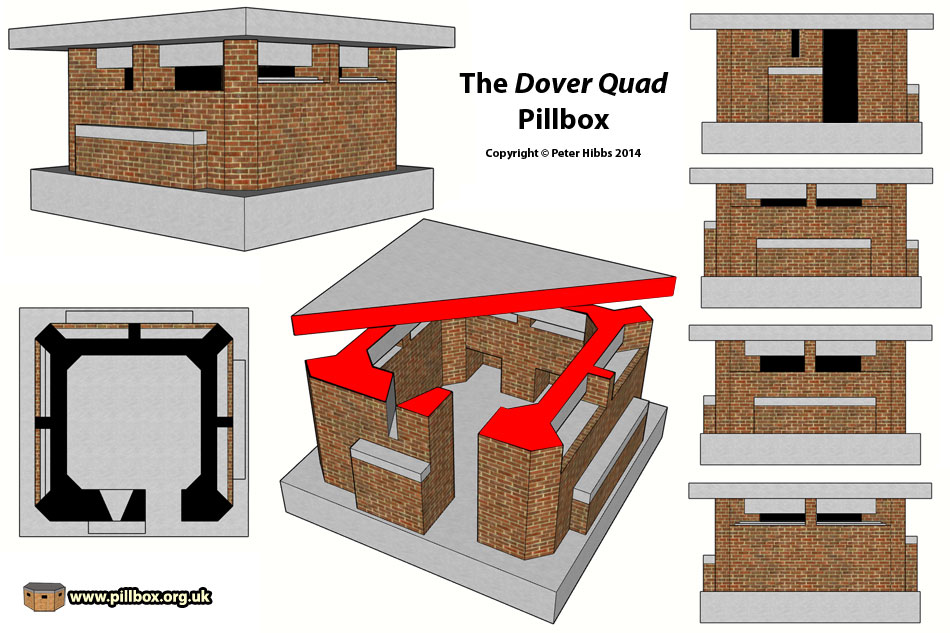

The Dover Quad design

Some like to criticise the Quad for being a 'death-trap' on account of the large embrasures some examples have, and I have to admit that these structures do look somewhat odd compared to other pillbox designs. But perhaps this is the wrong approach - if you compare the Quad to the landscape, its role and its ancestry instead of other pillboxes, you get a different conclusion.

The Quad incorporates many general design features, but variations can be seen according to their situation in the landscape.

The photo at right shows the differing sizes of embrasure; the ground outside slopes down from top right to bottom left and the pillbox itself is on a very steep precipice.

The right embrasure is 15cm high, the left 32cm; the latter seems dangerous, but allows a greater arc of fire along and down the slope.

Note the storage lockers built into the walls; these are a common feature and required a small wall to be built on the outside to maintain the overall wall thickness.

Other variations include modification of an embrasure to fit a Turnbull Mounting (below right) and a small version of the Quad built as an extension to an existing structure (below left).

The large overhanging roof is the Quad's most prominent feature; it gives the structure an amateurish 'lean-to' look and perhaps creates a dangerous bullet-trap, with the danger of rounds fired from downhill ricocheting inside. A concrete lintel above the embrasures would seemingly reduce this risk, however.

Being on high ground, the roof perhaps keeps bright sunlight and inclement weather out of the defenders' eyes.

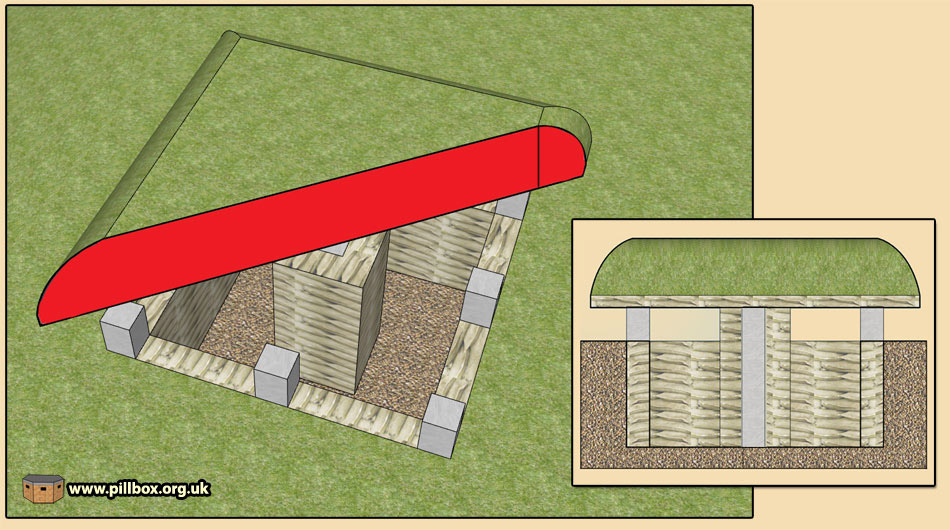

The graphic below is of a 3D model of a generic Quad with small and large embrasures.

The origin of the Dover Quad

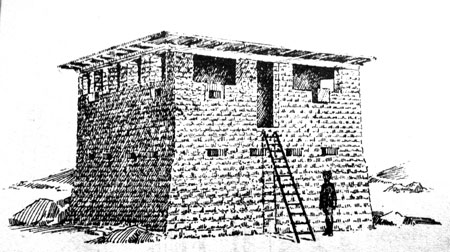

The graphic at right comes from the 1936 Manual of Field Engineering and shows a design of stone blockhouse built on the NW Indian Frontier.

Although it is a 2-storey design and very much larger, there is a vague resemblance to the Dover Quad.

The square shape and overhanging roof are familiar features, but if this diagram was an influence for the Quad design, I don't think it was the only one.

A possible clue is in the landscape where the Quad is most frequently found; hillsides.

The photo below shows a good example of a Dover Quad perched on the crest of a steep slope.

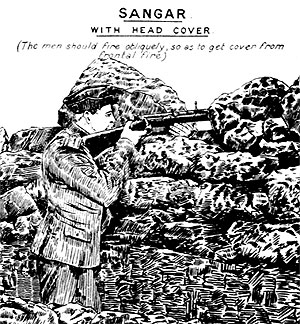

From this angle, the design reminds one of what the British Army still calls a sangar.

The term sangar is by no means new; it is essentially a temporary (or semi-permanent) fortification often employed as a sentry position or defensible outpost.

The 1908 manual Military Engineering (part 1): Field Defences includes diagrams of sangars used in South Africa, Afghanistan, Burma and NW India, stone being the main construction material.

A defensive wall could be built up on ground where digging was impracticable, or would affect the ability to command the surrounding area.

The 1908 diagram at right shows a sangar comprising a stone wall combined with a trench.

The 'head cover' is reference to the placement of rocks on the parapet, providing frontal protection while the rifleman fires at an angle.

Used in colonial warfare against an enemy less-well equipped than a modern European army, the sanger did not really need overhead cover in the form of a roof.

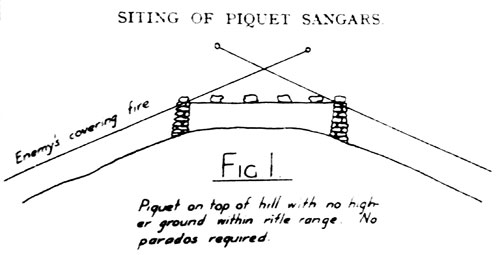

The 1936 manual (diagram at right) still advised on the employment of roofless sangars on high ground not commanded by enemy fire, and preferably where the enemy had no artillery.

This latter point might have been a bit optimistic in the event of invasion in 1940, but perhaps the Quad's concrete roof was a nod towards this.

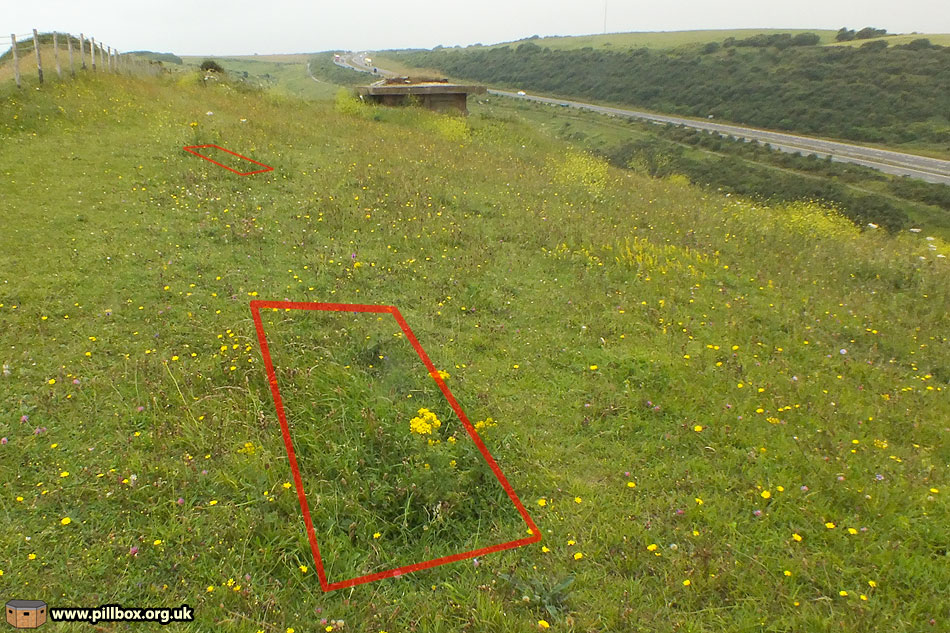

The photo below shows some of the Quad locations marked; note their location on high ground facing down into the valley. The field of fire from these positions is good across the sides and floor of the valley.

However, before we start pouring concrete on our Dover Quads, there's still a missing link we need to examine in this family tree.

Defence Post, June 1940

An interesting extract from an infantry war diary for 7th June 1940 reports that the Commanding Officer has

...invented a post that affords firing in every direction, with several of these scattered in the line of defence, each post is able to assist and cover their neighbouring posts. These have already been begun and hoped to be completed in a week or so.

Subsequent entries chart the progress of construction; some have been completed by June 10th and are being improved, with the majority of the work done by the 18th.

The diary appendix includes a diagram of the design, upon which I created a 3D model.

The post is essentially an earthwork; a hole 4.5ft deep with a floor 9x9ft is excavated and revetted - I've illustrated sandbag revetment here, as no particular material is specified.

Embrasures are formed by a breeze block being placed at the corners and halfway along each side. The plan labels these as "C.B.", which I assume stands for "Concrete Block" or "Cinder Block."

A central pillar of blocks surrounded by sandbags supports a roof made of sandbags laid on sheets of corrugated iron. A domed roof of earth is then applied giving a roof thickness up to 4ft.

The graphic below shows my interpretation of the plans.

The career of the Lieutenant-Colonel who "invented" this defence post is also of interest. Tracing him through the Army List I discovered that he had fought (and was wounded) as a 2nd Lieutenant in France and Belgium in 1918 and so would have been aware of the effect of modern artillery and small arms.

Staying in the army after the war, he served with the Royal West African Frontier Force (RWAFF) 1929-34, which leads me to think that his 1940 design for a defence post looks like a sangar as a result of five years spent in a 'colonial warfare' environment.

While we can't credit this officer for being the original inventor of the sangar, he does seem to have influenced its use away from its traditional colonial setting. However, look again at the photo of the valley above; its basic form is probably not too dissimilar to some of the African landscapes he was familiar with and when studying these defences, it's the landscape that dictates the methods of defence.

Phased construction?

Below is a side-by-side comparison of models of both the temporary structure and the Quad. The internal dimensions are reasonably similar.

But how do these two structures relate to each other? Only the Quads seem to survive, which leaves me to think that the original infantry-designed posts were rebuilt in more permanent materials at a later date. This idea is backed by the war diary; the quote above relates the "defence post" to the infantry battalion's southern area, but makes no mention of the term "pillbox".

By 14th June, the defences of a second, northern, area commence, being described as "Defence Posts and Pillboxes." We know that some Type 24 pillboxes were built in this second area, perhaps indicating that the defence posts were the sandbagged types and not the permanent Quad design at this time. A map dated around June 17th of the southern area defence posts appears to fit the locations of where Quad pillboxes stand today.

The fact that the defence posts were completed in a little over a week indicates they were not the brick-shuttered concrete Quads.

My feeling is, that assuming the infantry constructed their own defence posts (the war diary makes no mention of the Royal Engineers or civilian contractors), it may be that the work was not as good as it might have been and it was decided to redo the work permanently in concrete. As pits had already been dug and fields of fire calculated and coordinated according to the siting of these posts, it makes sense that the same design was reused with permanent materials in the same hole, rather than needing extra landscaping to accommodate one of the standard pillbox designs.

It would therefore seem that an earthwork design gave way to reconstruction in brick and concrete, giving us at least two phases of construction. This earth-to-concrete idea is not unique to this case; I've seen mention of trenches in East Sussex being reconstructed in brick and the Engineers redoing work previously done by the infantry.

It would be interesting to see if and when such a reconstruction was undertaken - I may leave this to others, as Kent is not my area of interest. However, there are some Quads that supposedly were left unfinished, so perhaps this was happening at the time hardened field defences were falling out of favour.

The return of earthworks

Pillboxes have far too much attention lavished on them though; their perceived 'dominance' as military defence structures in the UK effectively lasted little more than one year in a war that lasted for six.

Very little notice is taken of earthworks; concrete defences are often easy to see and perhaps provide more of a tangible link to the past than the shallow depression of a backfilled slit trench.

And here we have an earthwork redesigned in concrete; the Dover Quads are well-known, registered in the archaeological record and the subject of numerous photos on the Internet. They're pillboxes. They're interesting.

However, for each pillbox built during the invasion scare, many, many more slit trenches were dug. Pillboxes never achieved dominance over earthworks; slit trenches were never prohibited during the pillbox construction period in the way pillboxes themselves were from 1941.

The photograph below illustrates this point; on my first (and so far, only) visit to this Quad, I noticed the landscape evidence that everybody else missed; slit trenches. I must have located five or six of these in the vicinity of this pillbox, yet you won't find pictures of these online - until now.

Somewhat ironic, given that the pillbox itself began life as an earthwork!

The suitability of the Quad design on a modern European battlefield against artillery and aerial/naval bombardment was not tested at Dover. However, it is very easy to look at a single Quad on a hillside and decide it was going to be of little use. To do so is to remove it from its context; it was part of a network of defences, other pillboxes and earthworks whose fire plans were all coordinated to defend the landscape.

If you, in your mind's eye, subject a single defence work to attack by a squadron of Stukas before being assaulted by an entire Panzer Division you will get a very skewed view of things.

The Sangar today

What of the sangar? Is the Dover Quad design hopeless in modern warfare? No.

Read this blog post by Think Defence at: http://www.thinkdefence.co.uk/2012/12/the-expeditionary-elevated-sangar/ and you'll see that the British Army was still using the basic sangar design in recent decades in Northern Ireland, Afghanistan and Iraq. While facing more of an insurgent/guerrilla threat than combined armoured/airborne assault, the availability of sniper weapons and RPGs haven't necessarily reduced the modern sangar's embrasure size.

The basic sandbag/earthwork design with large embrasures and overhead cover is still in use - it's basically the Dover Quad design - it's just reverted back to its earthwork roots in many places.

Final thoughts

This has been an interesting piece of mini-research and it has confirmed a few things for me.

Firstly, that my methodology works outside of East Sussex; I'm still using the same combination of archive documents, tactical doctrine and fieldwork to uncover the story behind these defence works.

Secondly, the manner in which local variants or trends in design can occur. I've often noticed how outcrops of pillbox types occur in some areas, but not others.

Finally, the way in which evolution from earthwork to concrete happened and the importance of earthworks alongside pillboxes, despite the emphasis placed by so many on the latter.

As I say ad infinitum: if you don't understand earthworks, you can't possibly understand pillboxes!

That's enough from Kent for now - I'm heading back to East Sussex...

- Pete

Email:

Blog Latest

Bishopstone reveals its pillbox secrets

18 October 2021

Pillbox or Observation Post?

10 June 2020

Uncovering the hidden secrets of a pillbox

8 June 2019

Review of 2018

31 December 2018

Wartime Christmas in East Sussex (2)

24 December 2018

Jargon-buster

Embrasure

A loophole or slit that permits observation and/or weapons to be fired through a wall or similar solid construction.

Pillbox

Generic term for a hardened field defensive structure usually constructed from concrete and/or masonry. Pillboxes were built in numerous types and variants depending on location and role.

Slit trench

Small, narrow trench designed to provide protection against shrapnel and other battlefield hazards. Technically distinct from a weapon pit (which was intended soley as a defensive position) slit trenches were also used as defence works.

Turnbull Mounting

A steel framework that allowed a machine gun to be mounted in an embrasure of a pillbox or other defence work. The mounting could be used with a variety of weapons, such as the Vickers Gun and Bren Gun. Traverse and elevation gear allowed the weapon to be fired on fixed lines.

Type 24 pillbox

A six-sided (but not a regular hexagon) pillbox. The Type 24 is the most frequently seen pillbox in East Sussex, mostly along stop lines. It can be found in thin wall (30cm) or thick wall (1m) variants.

War diary

A record of events kept by all units from the point of mobilisation. A diary's contents vary enormously from unit to unit; some give detailed entries by the hour on a daily basis while others merely summarise events on a weekly/monthly basis.

This site is copyright © Peter Hibbs 2006 - 2024. All rights reserved.

Hibbs, Peter The Dover Quad - a colonial pillbox? (2024) Available at: http://pillbox.org.uk/blog/216739/ Accessed: 27 July 2024

The information on this website is intended solely to describe the ongoing research activity of The Defence of East Sussex Project; it is not comprehensive or properly presented. It is therefore NOT suitable as a basis for producing derivative works or surveys!