Uncovering the hidden secrets of a pillbox

Posted: 8 June 2019 20:02

This post is designed to highlight the sort of interesting features that are all too often overlooked in the study of anti-invasion defences. Despite being a well-known and photographed pillbox, the one we'll look at has hitherto not been subjected to anything more than casual observation.

The structure in question is in the overflow car park of the Bluebell Railway at Sheffield Park and until a couple of years ago, was covered in dense undergrowth. Admittedly, the vegetation probably prevented the sort of examination described here, but most pillboxes are not studied in the sort of detail required to uncover hidden details.

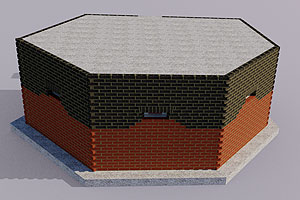

Our structure is an example of a Type 24 pillbox (DFW3/24) that was sited to cover Sheffield Bridge about 150m away. I was surprised to instantly spot an unusual feature that nobody seems to have mentioned before; check out the photo below:

Seen what I'm referring to?

If you look beyond the moss and vegetation that partly obscures the masonry, you'll see that the brickwork is two colours - and this was what initially sparked my interest in this pillbox. The structure is 30 courses of brick high; the upper 16 are almost completely of darker brown brick, while the lower 14 are in a brighter, red brick. (3 courses are below current ground level). Note how the red brick rises up by 3 courses where the embrasure on each wall occurs, creating a wavy line around the structure - this is a camouflage scheme!

This fits in with the camouflage concept of merging. For example, to make the pillbox blend into its surroundings, a two-tone camouflage scheme breaks up regular lines and places the embrasures within the areas covered by the darkest colour.

Looking at the photo below, we can see that the embrasures fall within the darker shade of brickwork. Note also the shadow cast by tree branches overhead; this seems to explain the brickwork scheme - it's trying to mimic and enhance this shadow effect. Given that there is an oak tree right beside the pillbox, it would apppear that the pillbox was deliberately sited under the cover of the tree as part of the camouflage scheme. This is important, as regulations stated that every pillbox should have a camouflage scheme prepared prior to construction. Even though I don't think the brickwork would fool the naked eye at ground level, even from 200m away, it may just tip the balance against aerial observation.

Another facet of camouflage is the remnants of black paint in the embrasures; this would tone down the white concrete. An interesting feature found in one of the embrasures appears to have been made by an acorn being pressed into the wet concrete!

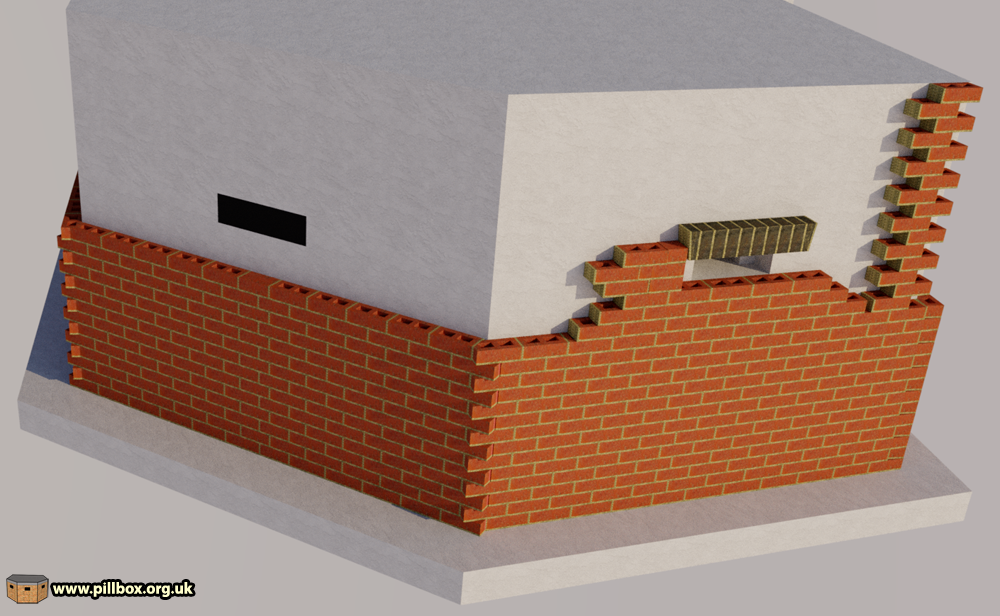

I constructed a 3D model of the pillbox to better illustrate the brickwork scheme; we'll come back to this model later on.

The XII Corps Stop Line

We've rushed into looking at camouflage without really looking at the pillbox design itself or the wider context.

Sheffield Park sits on the River Ouse which was established as a stop line in 1940. This basically entailed forming a defensive line on pre-existing landscape features in order to produce a continuous anti-tank obstacle. Pillboxes were constructed along stop lines, and in the case of the XII Corps line, mostly concentrating on strategic points such as bridges.

Archive research reveals that the line was being reconnoitred in August 1940 in order to site the defences. We also know that the Sheffield Park pillbox was built by a section of Royal Engineers under the command of a Captain Donald.

Design

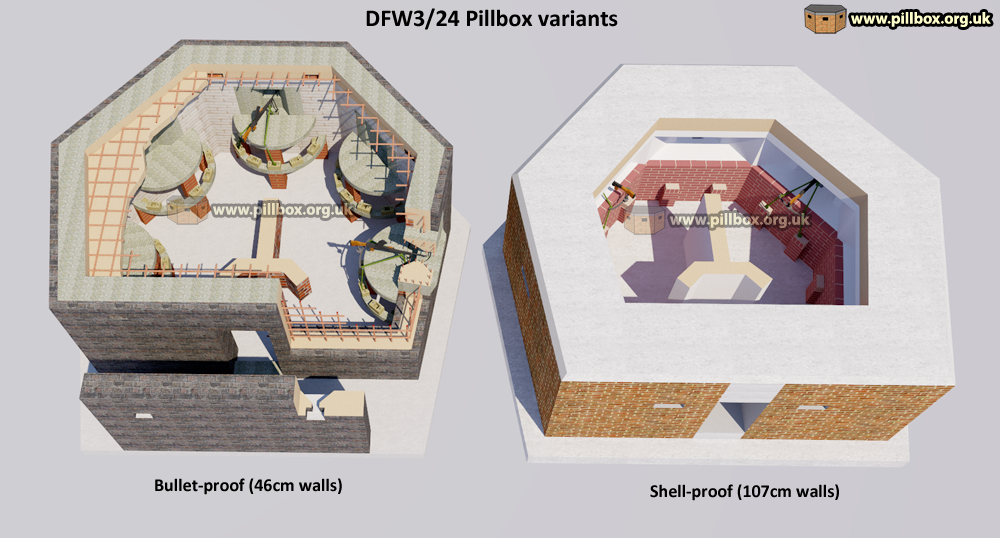

The structure is based on the DFW3/24 pillbox (shell-proof) design more commonly seen on the GHQ Stop line (Newhaven-Penshurst section in East Sussex), but with some differences. The graphic below shows the bullet-proof and shell-proof variants; the former illustrated is actually the neighbour of our pillbox and built by the same unit. Note how it has a detached blast wall with two embrasures.

The photo below shows that we have a Z-shaped blast wall protecting the entrance of our example; unusually for a Corps Line pillbox, neither this nor the rear wall of the pillbox itself has embrasures. Note the ventilation duct fashioned from brick on edge and lined with roof tiles above the door.

Inside, the interior layout is very similar to the standard shell-proof pillbox, with embrasures designed for the Bren gun tripod. The photo below shows that the brick piers that once supported a wooden bench are mostly missing. A standard Y-shaped brick blast wall partitions the interior.

But while our pillbox seems to follow the standard shell-proof design, there is a significant difference; one of the walls has no embrasure. While this omission was noted when the pillbox was initially recorded by the Defence of Britain Project 20 years ago, nobody has seemingly tried to establish the reason behind it.

We'll investigate the missing embrasure in due course, but another interesting feature is visible on this wall. Looking at the photo below you can see traces of a brickwork pattern under the whitewash. Initially, I thought that this was simply brick shuttering as is seen on the external face of the pillbox. Brick is commonly seen on interior walls too, with the intricate embrasure detail shuttered in wood, but then I noticed the detail in the enlarged inset; a piece of rebar exposed on the wall surface.

This piece of rebar is clearly encased in concrete, meaning that there's no brickwork present. Closer inspection shows that the lines of mortar are raised on the surface and not indented as would be the case with brickwork still extant. Therefore, the brick shuttering has been removed, leaving its impression in the concrete. This is further confirmed by the 'wrinkles' in the wall surface, notably visible at the top of the wall. This indicates that paper (probably the empty cement bags) was used to line the surface between the brick and the concrete being poured. If the shuttering was to stay in place, this would be pointless.

But why remove the brick shuttering? One advantage of brick is that it could be left in place and wouldn't need dismantling like wood shuttering. Look at the photo below that shows the internal blast wall and ceiling.

Note how the roof has been poured onto shuttering comprising some sort of sheeting (wood or metal) in 2ft squares. The panel highlighted in red shows that the blast wall was built after the roof shuttering had been removed. It also appears that the internal brick shuttering had been dismantled before the roof was shuttered and poured, as there is no impression of brick left on the ceiling.

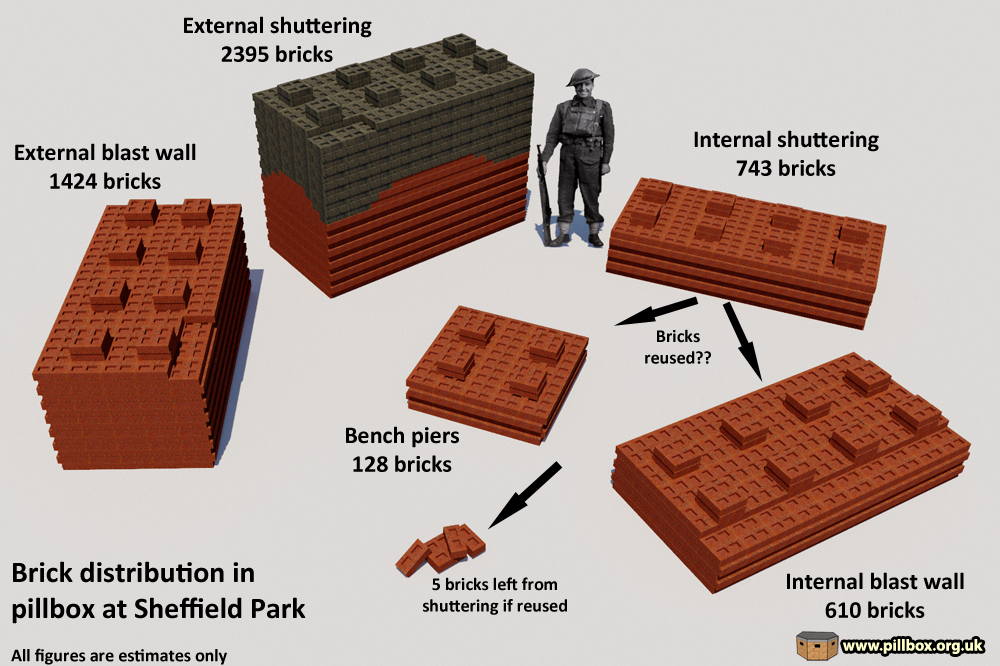

Now look at the blast wall; the brickwork is of a very poor standard as the face is not flush, notably the area outlined in green. Note the mortar to the right of the blue line, roughly slapped on to fill gaps and form the corner of the wall. The question is, was it constructed using bricks recovered from the shuttering? There is no definite evidence, but by my estimation, the internal blast wall comprises 610 bricks, whereas the internal shuttering (calculated by measuring the surface area of the walls) would require about 743. Add to this 128 bricks to build the piers that support the wooden bench, and you have only a handful of bricks left over. This is pure speculation on my part, but I can see that it actually makes sense to do this. Yes, it may be time-consuming to remove brick shuttering and clean the bricks off, but turn this around and think about what effort and resources are saved. You save 700+ bricks and avoid the need to transport an extra 2 tons of materials to the construction site.

The graphic below illustrates the estimated amount and distribution of bricks throught the structure. These stats have been generated by the software counting how many times I used each type of brick in each part of the 3D model.

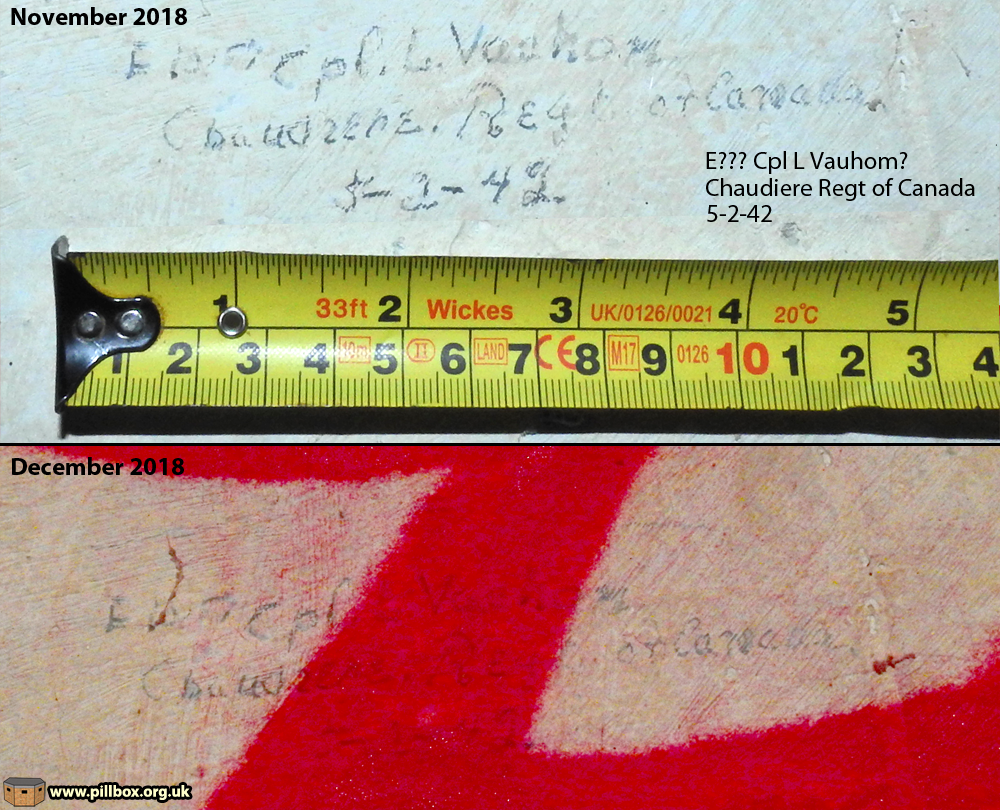

On the subject of walls, this is a good point to note the presence of some wartime graffiti as shown below. Sadly, the pillbox was heavily vandalised with modern graffiti in late 2018 and the wartime scribble by a Canadian soldier was all but obscured by it. This act was reported as a heritage crime.

The missing embrasure

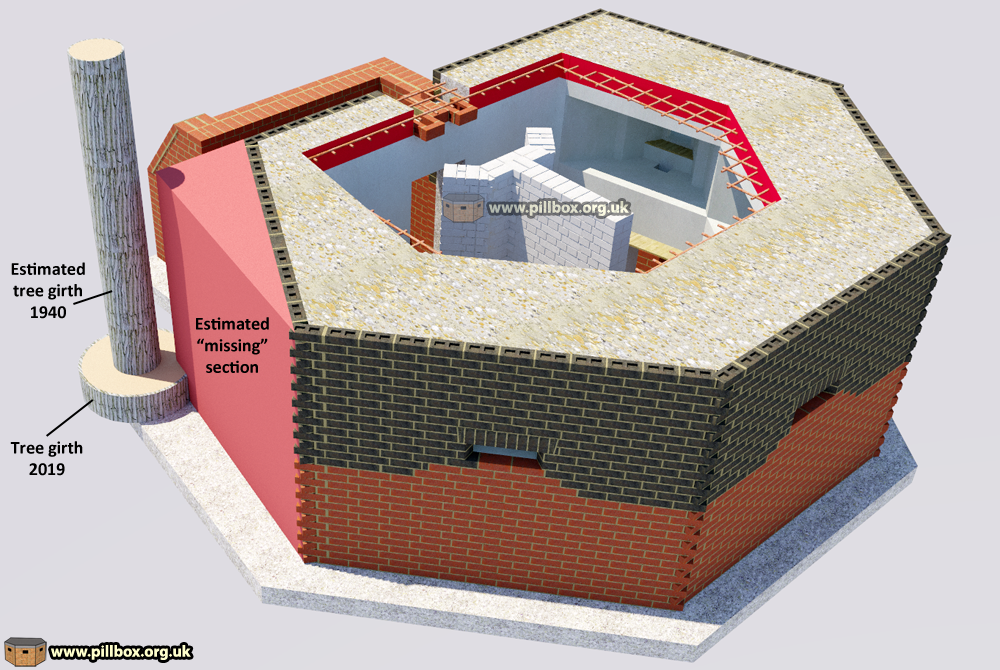

The burning question is: why does one wall have no embrasure? My original thought was that the oak that provides the pillbox's camouflage would be in the line of fire and so the builders simply omitted the embrasure as an unnecessary feature. However, given that the tree would have been only half as thick in 1940, I don't think it impeded a useful arc of fire had the wall been loopholed.

Not having an immediate explanation for the missing embrasure I decided to get some photos from my 5m selfie stick; it was then that the mystery began to unravel. Look at the photo below; does anything seem odd?

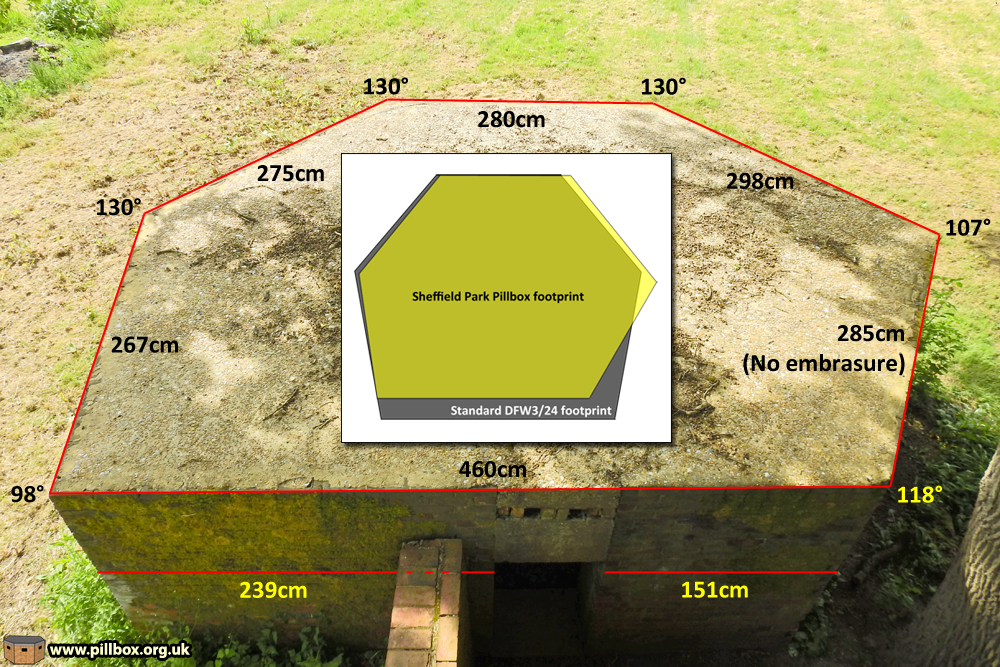

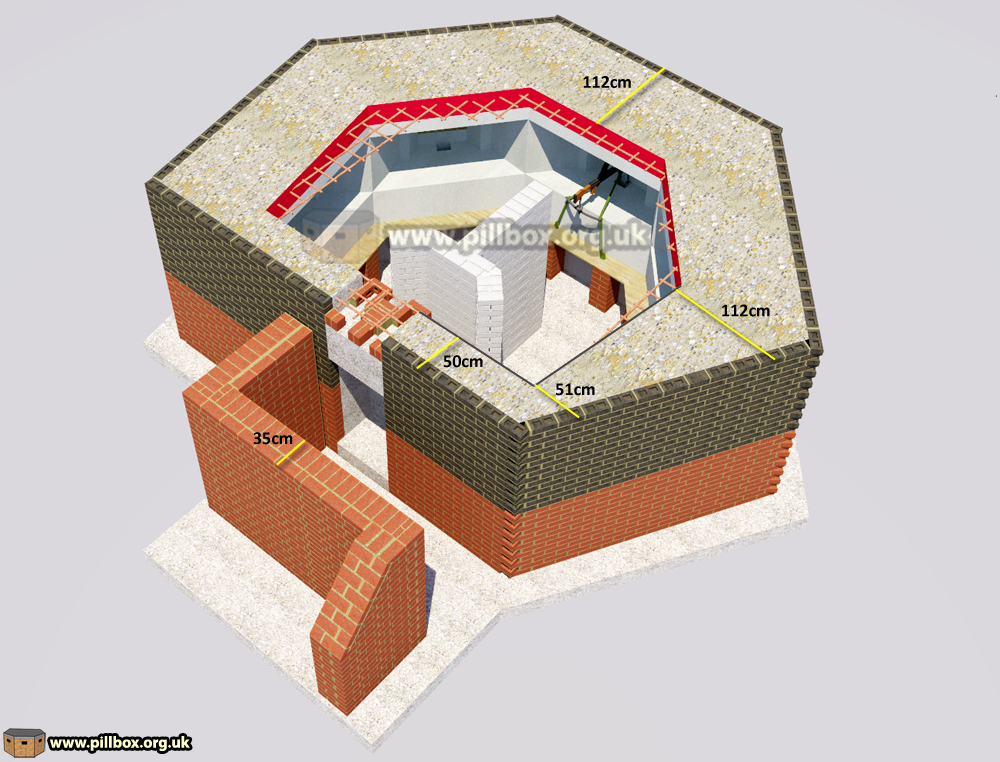

The above photo led to my doing a thorough survey of the pillbox. Let's add some basic measurements to illustrate the issue. Look at the measurements starting at bottom left in the photo below and follow them round towards the tree. The wall that has no embrasure is where the geometry all goes wrong.

It's not unusual for there to be discrepancies in pillbox geometry; the urgency and speed of construction inevitably meant that a structure may not be perfect, but this pillbox is in a league all of its own. Just look at how offset the door is from the centre and it does appear that the wall missing an embrasure is trying to avoid the tree. The graphic shows our pillbox's footprint overlaid on that of a geometrically-correct standard DFW3/24. From this we can also see a difference in the front-rear dimensions that we need to account for.

The 3D model

I decided to build a detailed 3D model because I wanted to record the camouflage brick pattern and also to understand what was going on with the blank wall. Although the Sketchup software I use allows textures (eg, a photograph of a brickwork pattern) to be applied to a model, I felt it was worth building using individual bricks and doing the job properly.

Early on it seemed sensible not to attempt to literally replicate each single brick, as this would have taken forever and probably seen me abandon the project. No, what was important to me was to record the basic arrangement of bricks in the bond, but ensure that the bricks that rise to below the embrasure to effect the camoufage wavy line were accurate.

I recorded two representative alternating courses, but found that the stretcher bond was actually quite regular and predictable anyway. Most brick lengths were 23cm with some 19-22cm, with a number of half bricks and fragments used in odd corners.

It's interesting to note that by using stretchers, the length of each course is actually half a brick too long for the length of the wall, leading to the "interlocked fingers" effect on each corner on alternating courses. On other pillboxes sometimes a half brick is used to foreshorten the course and in some cases, bespoke angled bricks appear to have been used.

The graphic below shows the completed model and how badly wrong things are with the geometry. It's so bad, I took the basic measurements several times to make sure I wasn't getting it wrong. We can see that the 50cm rear wall accounts for the difference in the front-rear axis compared to the standard design. But we now have the answer to the blank wall; it's not thick enough to accommodate the standard embrasure design.

What went wrong?

The first question is whether the original intention was to build the standard DFW3/24 design or not; the photo below hints this was the case, as the blank wall appears to stop way short of the foundation. The concrete has been broken up by the tree and is covered by vegetation and earth, but as far as I can tell, the correct design was planned for. It leads me to think that a miscalculation caused a drastic modification on the job.

Even though the tree would not have blocked the view from an embrasure, I still believe the error in construction originates from it. The graphic below shows an extrapolated section in red to denote the "missing" mass. The tree is shown in two states; the outer ring denotes the rough size of the trunk today, the inner is a rough estimation of the size in 1940. The estimated wall is only 6 inches from the estimated size and location of the oak. (Note my multiple use of "estimation"; it is nothing more than that.)

My theory is that in a conscious effort to utilise the tree camouflage to maximum effect, the foundation was laid too close to it. The tree today leans over towards the pillbox; was it leaning too much for the intended height of the roof in 1940? Was a low hanging branch in the way? As it would appear that the oak was a vital part of the camouflage, it would be counterproductive to remove it or significant branches. Whatever the reason, it required foreshortening the rear wall by 3 feet and cutting the corner off the intended design.

Camouflaging the cock-up?

It sounds a bit conspiratorial, but part of me thinks that the error was subject to some camouflage of its own to prevent the occupants from realising the weakness in the structure. Some professional pride of the Royal Corps of Engineers was probably also at stake.

So how was the error covered up? Firstly, the omission of a loophole in the blank wall. The wall was not of uniform thickness and any loophole would give the game away. But for me, the external blast wall is the real sleight-of-hand.

It was not until I saw the high-rise photograph above that I realised what the blast wall was doing. Standing inside the pillbox, the doorway is in the centre (give or take 2cm). Standing outside, the fact that the blast wall springs off the rear wall of the pillbox hides the fact that the entrance is very obviously not central in the exterior wall. While many other Corps line pillboxes have blast walls that abut the main structure, it is perhaps convenient that using the technique here is beneficial to covering up the Achilles heel. Unless you really study the pillbox architecturally and actually survey all the angles, you probably would never notice the cock-up!

Conclusion

We've taken a detailed look at just one pillbox and uncovered some of its story, both from the archive documents and detailed study of its design and construction. We've seen how that, although a pillbox may be built to a basic design, no two are ever the same. Next time you're looking at a pillbox, instead of taking a few snaps to post on social media before moving on to the next one in the line, stop and take a closer look - you never know what you'll discover!

- Pete

Email:

Blog Latest

Bishopstone reveals its pillbox secrets

18 October 2021

Pillbox or Observation Post?

10 June 2020

Uncovering the hidden secrets of a pillbox

8 June 2019

Review of 2018

31 December 2018

Wartime Christmas in East Sussex (2)

24 December 2018

Jargon-buster

Defence of Britain Project

A large project run by the Council for British Archaeology (CBA) 1995-2002, collecting data on 20th century military structures submitted by a team of some 600 volunteers. The result was a database of nearly 20,000 records which is available online. The anti-invasion section of the database contains nearly 500 entries for East Sussex.

Embrasure

A loophole or slit that permits observation and/or weapons to be fired through a wall or similar solid construction.

Loophole

Embrasure

Pillbox

Generic term for a hardened field defensive structure usually constructed from concrete and/or masonry. Pillboxes were built in numerous types and variants depending on location and role.

Stop line

A physical continuous anti-tank barrier, normally a river and/or railway line, often defended by pillboxes. Stop line crossings (roads, railways and bridges) were to be made impassable.

Type 24 pillbox

A six-sided (but not a regular hexagon) pillbox. The Type 24 is the most frequently seen pillbox in East Sussex, mostly along stop lines. It can be found in thin wall (30cm) or thick wall (1m) variants.

This site is copyright © Peter Hibbs 2006 - 2024. All rights reserved.

Hibbs, Peter Uncovering the hidden secrets of a pillbox (2024) Available at: http://pillbox.org.uk/blog/250548/ Accessed: 27 July 2024

The information on this website is intended solely to describe the ongoing research activity of The Defence of East Sussex Project; it is not comprehensive or properly presented. It is therefore NOT suitable as a basis for producing derivative works or surveys!