My largest find

Posted: 30 December 2010 18:10

A chance conversation led to an interesting afternoon's investigation and the largest piece of surviving evidence I've found to date.

It started some weeks back after a chat with a friend who recalled a series of air landing strips being built near where he lived as a child during the war.

I thought no more about it until a few fragments of information came together this morning. Firstly, I found a mention in a document of an Airfield Construction Group stationed at the location in question.

Secondly, I mentioned this on the offchance to my father, who then volunteered for the first time to me (though everyone else in the family seems to have known) the information that he remembered some airstrips there back in the 1950's.

He recalled at least three, although he wasn't sure if they were part of the same strip; he even souvenired a piece of bitumen from the site many years ago, although where it is now is anyone's guess.

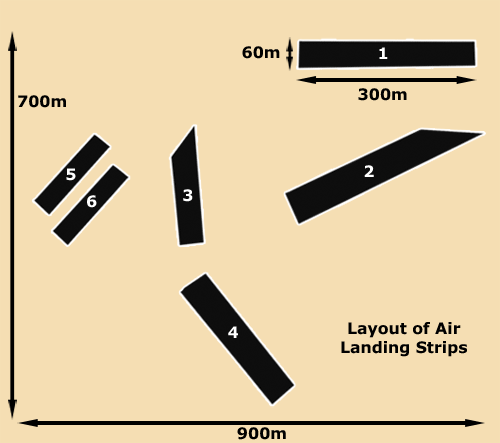

This revelation prompted me to rifle through some aerial photographs and confirmation of the airstrips was provided; the arrangement is shown at right.

By importing the photo into Google Earth, I used the measure tool to get some dimensions.

I've numbered the strips 1-6; 5 and 6 are only speculative at this point, as they just show up in outline on the photo - I'll return to these later.

Number 3 is also speculative at the moment but less so than 5 and 6; it does appear to be a straight-edged feature of similar appearance to numbers 1,2 and 4, which tie in with my dad's memory.

Several questions spring to mind when looking at this plan; why so many seemingly separate airstrips in such a small area, and did any aircraft ever land here?

The next step was to go looking for evidence in the landscape.

Having got the map out, I jumped into the car and went in search of evidence that I knew still existed at least into the 1950's.

Staggering through some dense woodland and gorse, I suddenly found myself in a long airstrip-shaped clearing, covered in a very soggy, sticky clay substance. This was the area of airstrip no.1.

The key evidence apart from the location and clearing can be seen in the foreground of the photo above; pieces of bitumen.

The piece below was the largest I was to see all day; shattered by 70 years of frost and melted and bubbled by hot sun, it was not in good condition.

However, a lot of evidence was to be found by a close examination of it. It appears that the airstrip surface was built up in layers of bitumen as indicated below, a total of at least 35mm, although this sheet may not represent the full thickness. The layers don't appear to be even and Dad did say he didn't remember the surface being overly flat.

An interesting feature evident below is the cross-hatch pattern in the bitumen; prehaps hessian was used as a binding surface between layers or applied as camouflage to the upper layer.

Having finished here and sinking even further into the mud, I made a quick recce of strips nos. 5 and 6, only to find the area they were in to be a ploughed field. My original contact had mentioned piles of pierced steel planking (PSP) in the vicinty of this field and this is why I speculate the presence of two strips in conjunction with the outlines on the aerial photo. The remaining PSP was apparently 'borrowed' by local farmers after the war.

I had enough time to investigate strip no.2 and after another slow advance through forest and thicket, I arrived at the very end. The photo below shows the strip starting where the line of bracken suddenly stops.

This area was interesting; the grass indicates where the bitumen still lies undisturbed. Prodding with my walking pole pierced about an inch of clay/mud/moss and met with a solid thud.

I was unable to actually see any of the surface here; scraping back a small area of this 'turf' revealed a hard substance, but the black colour was not showing due to the muddy water and even a drenching from my water bottle could not wash the mud out.

So why were these airstrips built here, why are they seemingly so small and squashed into such a cramped area?

The answer lies in the nature of the use of the land by the army; it is listed as a training area. The assumption is, therefore, that the fragmented pieces of landing strip were the product of training exercises or were perhaps developing experimental techniques.

The fact that so many strips are in a small area does not necessarily rule out aircraft operating from them, however. The longest strip is 300m; the Lysander certainly had a good reputation for short take-off and landing, but a search of the modern literature reveals no mention of this site.

My next visit to the National Archives will include the war diary of the Airfield Construction unit in question. I can always hope that it'll include detailed accounts and maps to explain what's going on here, but I suspect it'll have nothing of the sort and will be the uninformative type of document that describes many months of activity on a single page.

Otherwise, another trip up to the site to locate the missing strips is required, as is a copy of the relevant engineering manual on airfield construction.

- Pete

Email:

Blog Latest

Bishopstone reveals its pillbox secrets

18 October 2021

Pillbox or Observation Post?

10 June 2020

Uncovering the hidden secrets of a pillbox

8 June 2019

Review of 2018

31 December 2018

Wartime Christmas in East Sussex (2)

24 December 2018

Jargon-buster

War diary

A record of events kept by all units from the point of mobilisation. A diary's contents vary enormously from unit to unit; some give detailed entries by the hour on a daily basis while others merely summarise events on a weekly/monthly basis.

This site is copyright © Peter Hibbs 2006 - 2024. All rights reserved.

Hibbs, Peter My largest find (2024) Available at: http://pillbox.org.uk/blog/216676/ Accessed: 27 July 2024

The information on this website is intended solely to describe the ongoing research activity of The Defence of East Sussex Project; it is not comprehensive or properly presented. It is therefore NOT suitable as a basis for producing derivative works or surveys!